It was seventy-five years ago this month: 8 May 1945 – VE (Victory in Europe) Day – was one that remained in the memory of all tho who witnessed it. It meant an end to nearly six years of a war that had cost the lives of millions; had destroyed homes, families, and cities; and had brought huge suffering and privations to the populations of entire countries.

Millions of people rejoiced in the news that Germany had surrendered, relieved that the intense strain of total war was finally over. In towns and cities across the world, people marked the victory with street parties, dancing and singing.

But it was not the end of the conflict, nor was it an end to the impact the war had on people. The war against Japan did not end until August 1945, and the political, social and economic repercussions of the Second World War were felt long after Germany and Japan surrendered.

With Berlin surrounded, Adolf Hitler committed suicide on 30 April 1945. His named successor was Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz. During his brief spell as Germany’s president, Dönitz negotiated an end to the war with the Allies – whilst seeking to save as many Germans as possible from falling into Soviet hands.

A German delegation arrived at the headquarters of British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery at Lüneburg Heath, east of Hamburg, on 4 May. There, Montgomery accepted the unconditional surrender of German forces in the Netherlands, northwest Germany and Denmark. On 7 May, at his headquarters in Reims, France, Supreme Allied Commander General Eisenhower accepted the unconditional surrender of all German forces. The document of surrender was signed on behalf of Germany by General Alfred Jodl and came into effect the following day.

Soviet leader Josef Stalin wanted his own ceremony. At Berlin on 8 May, therefore, a further document was signed – this time by German Field Marshal William Keitel. Dönitz’s plan was partially successful and millions of German soldiers surrendered to Allied forces, thereby escaping Soviet capture.

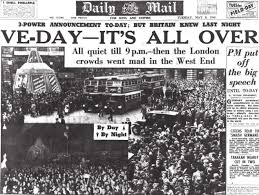

The announcement that the war had ended in Europe was broadcast to the British people over the radio late in the day on 7 May. The BBC interrupted its scheduled programming with a news flash announcing that Victory in Europe Day would be a national holiday, to take place the following day. Newspapers ran the headlines as soon as they could, and special editions were printed to carry the long-awaited announcement. The news that the war was over in Europe soon spread like wildfire across the world.

A national holiday was declared in Britain for 8 May 1945. In the morning, Churchill had gained assurances from the Ministry of Food that there were enough beer supplies in the capital and the Board of Trade announced that people could  purchase red, white and blue bunting without using ration coupons. Various events were organized to mark the occasion, including parades, thanksgiving services and street parties. Communities came together to share the moment. London’s St Paul’s Cathedral held ten consecutive services giving thanks for peace, each one attended by thousands of people. Due to the time difference, VE Day in New Zealand was officially held on 9 May.

purchase red, white and blue bunting without using ration coupons. Various events were organized to mark the occasion, including parades, thanksgiving services and street parties. Communities came together to share the moment. London’s St Paul’s Cathedral held ten consecutive services giving thanks for peace, each one attended by thousands of people. Due to the time difference, VE Day in New Zealand was officially held on 9 May.

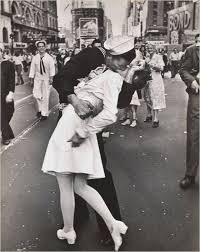

In the United States of America, the victory was tempered with the recent death of President Roosevelt, who had led his country through the war years. His successor, Harry S. Truman, dedicated the day to Roosevelt and ordered that flags be kept at half-mast – as part of the 30-day mourning period. Despite this, there were still scenes of great rejoicing in America: in New York, 15,000 police were mobilized to control the huge crowds that had massed in Times Square.

Not everyone celebrated VE Day. For those who had lost loved ones in the conflict, it was a time to reflect. Amidst the street parties and rejoicing, many people mourned the death of a friend or relative, or worried about those who were still serving overseas. For many of the widows the war had produced the noise and jubilation as people celebrated VE Day was too much to bear and not something they could take part in.

There was also an air of anti-climax. The hardships of the war years had taken their toll on many people and left them with little energy for rejoicing. In Britain, the strain of air raids, the strictures of wartime life and the impact of rationing all left their mark on a weary population who knew there were more difficulties yet to endure.

For members of the Allied forces who were still serving overseas on VE Day, the occasion was bittersweet. Although it meant victory in one theatre, the war was not yet over in the Far East and Pacific. The battle conditions there had been some of the toughest of the war. In May 1945, thousands of Allied servicemen were still fighting in the Far East and thousands more were held as prisoners of war in terrible conditions.

The final months of the war in the Pacific saw heavy casualties on both sides, but ultimately ended in victory for the Allies. Japan’s leaders agreed to surrender on 14 August and the act of surrender was signed on 2 September. For people in Britain, the end of the fighting didn’t mean an end to the impact of the war on their lives. Although many things slowly began to return to normal, it took time to rebuild the country and shortages were still felt: clothes rationing lasted until 1949 and food rationing remained in place until 1954. Peace brought its own problems. The huge economic cost of the war resulted in post-war austerity in a practically bankrupt Britain and the far-reaching political effects of the conflict ranged from the fall of the British Empire to the onset of the Cold War.

Note: Post 24, like most of the businesses in the area, have suspended all activities requiring public gatherings which would pose a health threat due to COVID-19. As a result, the Post regrets that Memorial Day services at Pine Grove Cemetery and the annual Memorial Day Parade will not be conducted this year.