The American Legion was founded in 1919 by veterans returning from Europe after the First World War, and was later chartered under Title 36 of the United States Code. The first American Legion Meeting held was at the Weirs of New Hampshire.

NAMING THE POST

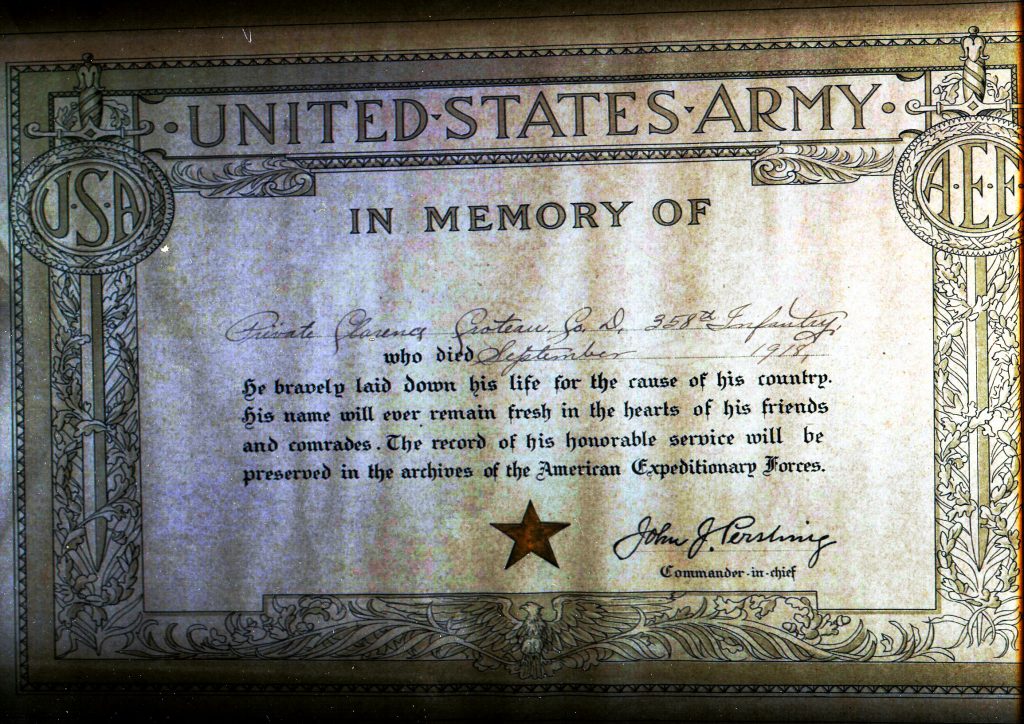

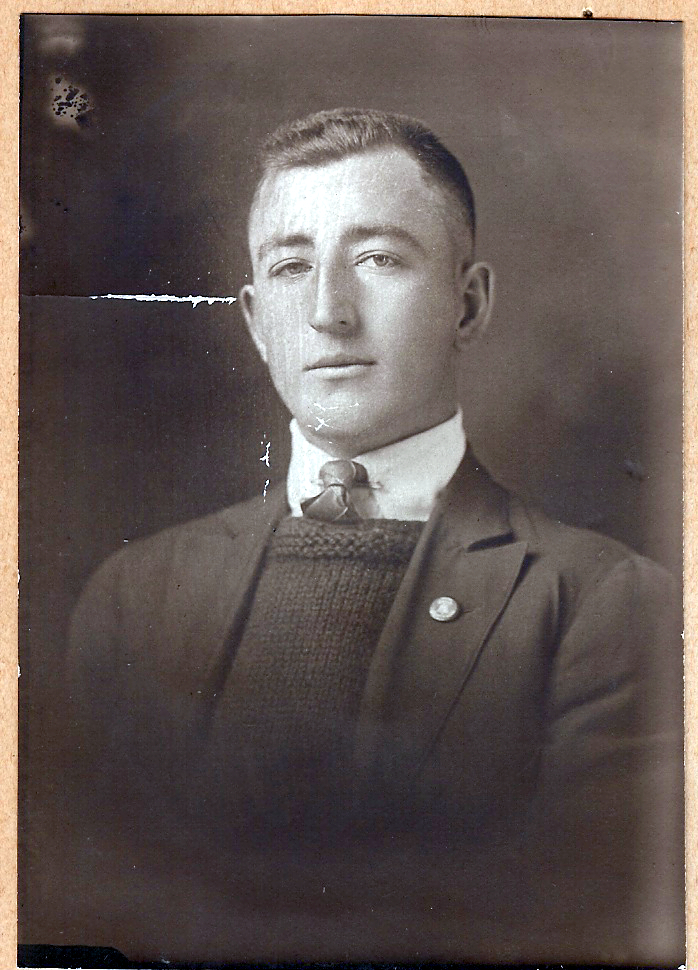

CLARENCE CROTEAU On 23 July 1919, Marlborough Post 24 was organized. The Post was originally named for Clarence J. Croteau, a Marlborough resident born in 1896. Private Croteau enlisted in the Army in 1917 and deployed to France as part of the American Expeditionary Force during the First World War. He was a member of Company D, 358th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division and participated in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. This particular offensive began half an hour before midnight on 25 September 1918, less than two weeks after the start, and only ten days after the finish of the St Mihiel offensive. Thirty-seven French and American divisions launched this new and even more ambitious offensive. It was against the Argonne Forest and along the river Meuse. As part of the preliminary bombardment that night, the American Expeditionary Force fired eight hundred mustard gas and phosgene shells, incapacitating more than 10,000 German troops and killing 278. The six-hour bombardment continued throughout the night. Then at 0530 on the morning of 26 September 1918, more than seven hundred tanks, followed closely by the infantry, driving the Germans back three miles. Clarence J. Croteau died in France on 26 September 1918 at the age of 22.

CHARLES BEVERLY COUTTS In 1946, Post membership passed a resolution to change the name of the Clarence J. Croteau Post to the Croteau-Coutts Post to also honor another Marlborough resident, Second Lieutenant Charles Beverly Coutts, an Army Air Corps Bombardier, who died in the line of duty during the Second World War in the Pacific Theatre of Operations. Charles was a member of the 61st Bomber Squadron, 39th Bomber Group, Very Heavy and was reported missing on 28 April 1945. Charles was born on 14 August 1924 to William Coutts and Mary Dutton Coutts. His father’s occupation was listed as a clerk born in Scotland and his mother was born in Hancock.

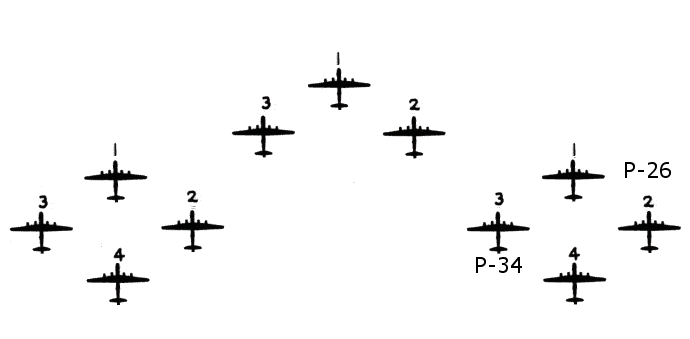

Accounts of the loss of Coutts aircraft (P-26) read as follows:

“On the 28April 1945, one composite squadron of the 39th of 12 aircraft, along with other bomber groups of the 314th Wing, struck the Kushira Airfield. Eleven planes bombed the primary. The other, having arrived late at the assembly area joined the 19th Group and bombed Kanoya Airfield.

The weather was clear, and the bombing altitude was around 17,000 feet. So preoccupied with enemy aircraft, results at Kushira were reported as unobserved. Strike photographs indicated good to excellent, while results of the 19th were judged as only fair.

Enemy opposition was the heaviest encountered to date. Some 50 aircraft were present in the target area, and the enemy pressed 30 to 40 attacks on the formation. Gunners claimed nine destroyed, four probables, and four more damaged.

One plane ditched that day with 11 men and one passenger. This was Orionchek’s Crew P-26 with Clarence Beevers, engineer of P-31R on his orientation flight. P-26 had been rammed over the target by enemy aircraft; however, it is believed ditching was due primarily to failure of the number 4 engine. Pulley’s crew would report the location of the ditching and all 12 men were in lifeboats. Bad weather prevented a rescue; the men disappeared about two days later.” Charles Beverly Coutts was 21 years old at the time of his death.

Rowland Ball, Navigator, on Crew 3’s “City of Montgomery” recalls this of the loss of Original Crew P-26 in the following account. This account comes from an exchange of email between Rowland Ball and Robert Hosford, Jr. Hosford, Sr. was Radar Observer on Crew 3.

“We (P-3) had mechanical difficulties of some kind and did not get to the rendezvous point in time to leave with our squadron. The 61st Squadron was just leaving so we joined up them. I looked out to our right at the plane that was flying beside us and saw that it was P-26 which was the plane that two good friends of mine were in. F/O David Donahoo was the navigator and Corporal Conrad Vogt was the radio operator. We had known David and his wife when we were in Radar School in Boca Raton, Florida. My wife and David and his wife would go for long walks along the beach in the afternoons late. Conrad Vogt was from my home town, Victoria, Texas and we went to high school together. He was a year behind me, but his sister Dorothy was in my class. So we went over the target with the 61st Squadron. We had received only moderate flak and after we dropped our bombs we noticed a lone Jap fighter plane at 9 o’clock level that was out of range of our guns. We believe he was in contact with Japanese ground based anti- aircraft batteries and was giving them our altitude, speed and heading. After a few minutes he speeded up and got out in front of our formation. Then he turned sharply and headed right for our formation. Up to this point we had not heard of the Kamakazies who would dive their planes into one of our planes or one of our ships and commit suicide by bringing us down by ramming us. As soon as he got within range all of the gunners in the flight opened up on him. What was alarming to us was the fact that it looked as though we were the one he had chosen to ram. As he got closer he must have gotten hit and killed because he kind of rolled a little to the left and we could see that he would miss us. But, this threw him right into P-26 who was right next to us and he hit them. He took about six feet of their right wing off and then he spun on down into the sea.

Although P-26 was in bad trouble the pilot did have some control of the plane. Rather than bail out evidently they chose to ditch. Or, they might not have had time to bail out because they were going down pretty fast. The pilot did a super job of ditching. With part of his right wing gone he did get down without crashing. The plane did break in half as it hit the water and the front end went under the water, but it popped back up right away. The rear half did not go under.

We went down right after them to kick out our emergency gear. I called the nearest sub, but there was not one within about 50-75 miles. We flew low and kicked out our stuff and we could see the guys climbing out of the pilot’s window. I had a K-6 camera on board to help make a Radar map of the coastline of Japan. I got this camera and took some pictures of the guys that were in the front end of the airplane standing on the wing of the floating aircraft trying to get into the big dinghy that they had popped out of its storage place on the left side of the fuselage. We kept circling them and I took some more pictures of them after they all got into the dinghy. There was no activity at all from the rear section of the plane. I guess they must have all been killed or knocked out, but we never did see any of them try to get out. We circled them for quite a while and there still had not been a sub show up. We were beginning to get a little low on gas and we still had about eight hours of flying time left to get back to Guam. We hated like the devil to go off and leave them, but we had no other choice. So, we waggled our wings at them and departed for home.

When we got back to Guam I went over Group Headquarters to see if they had any word on these guys. They did not. I went back every day for a week and they never did get any information on them. I am sure that Japs came out after the raid and strafed these guys and killed them. They usually would do this. After every raid they would send out planes to look for downed airmen and shoot them up.

It was quite a blow to loose two good friends at one time. I went over to the Photo Section and they gave me prints of the pictures that I took and after the war was over and I got back home I went over to Mrs. Vogt’s house and gave her and Dorothy a picture of Conrad along with the other guys in the dinghy. I explained everything that had happened and they were appreciative because they had no knowledge at all of what had happened to Conrad. They had just received the telegram saying that he was missing in action.”

2nd Lt Jim A. Mc Candless, Radar Observer; 2nd Lt Aaron M. Kopit, Pilot; 1st Lt Alexander Orionchek, Airplane Commander; 2ND LT CHARLES B. COUTTS, Bombardier; F/O David P. Donahoo, Navigator.

Back Row (standing) L to R:

Cpl Conrad E. Vogt, Radio Operator; Cpl Marvin H. Long, Right Gunner; #5 Cpl John C. Sprosty, Tail Gunner; All others unknown at this time.

Not yet identified in crew photo:

T/Sgt Robert L. Addleman, Flight Engineer; Sgt William L. Wood,

CFC Gunner; Cpl Albert P. Tomasetti,Left Gunnr

The following account comes from F/O Morris Yancey, Flight Engineer, P-34.

“Crew No. 26, Alexander Orionchek, 1st Lt, Airplane Commander went down 28 April 1945. The mission was Kushira Airfield.

Crew No. 34 was flying in the number three ship in the second sortie. Crew No. 26 was flying in number two ship in the same sortie. Shortly after dropping our bombs, a Japanese fighter rammed the right wing of Crew No. 26 ship knocking off about “20” feet of the wing. We were flying at about 22,000 feet at the time. No. 26 crew immediately started to fall. We waited to see if they would crash or level off before deciding what action to take. Fortunately, they leveled off at about 12,000 feet. We were still over land at the time. When we say that they were not going to crash, we went down to “buddy” them as they were being attacked by three Japanese fighters. Their gunners with our help managed to drive the fighters off. The dive from 22,000 feet to the 12,000 feet altitude was my fastest in a B-29. I could not operate the cabin pressure not to have our ears feel the pressure.

Crew No. 26 limped along, with Crew No. 34 tagging along, until it was estimated to be 90 miles from the Japanese coast. The plane had been gradually loosing altitude until it hit the water. Crew No. 34 circled the area and counted the men in the lifeboat. There were 12 men in the plane and all had gotten in the lifeboat. Henry Snow was flying with Crew No. 34 for experience as his crew had just gotten over from the states. His flight engineer was flying for the same reason with Crew No. 26

Crew No. 34 threw out all of their emergency equipment, the “Gibson Girl” radio, life rafts, food and everything else that could be used by the downed crew.

While circling the life boats, our navigator and radio operator were contacting the Super Dumbos in the area. It was necessary to pinpoint our location to let the Super Dumbos know where we were. Our location was calculated from a fixed station in the Aleutian Islands and Hawaii. By the time this had all taken place and our fuel was getting low. The Super Dumbo said it would be approximately 45 minutes before they could arrive at our location. It was determined that we could stay in the area approximately 25 minutes longer without jeopardizing our ability to get to Iwo Jima. These transmissions, of necessity, being so close to the Japanese coast had to be in code. After remaining in the area approximately 30 minutes we headed for Iwo Jima. In an effort to gain more airtime we ejected our bomb bay gas tank and removed and jettisoned the ammo from all the gun turrets. When we landed on Iwo Jima, the chart indicated all the gas had been used. No gas was visible in the tanks. It was late in the day when the report of the downed crew was made on Iwo Jima. Three crews were sent out early the next morning to locate the

P-26 crew in their life boats. These crews were Crew No. 23, Joseph J. Semanek, AC, Crew No. 28, Charles B. Miller, AC and Crew No. 21, William J. Senger, after spotting a downed crew in a life boat and contacting a rescue, the three planes returned and the search called off. When the rescued crew was identified later it was not that of No. 26 Orionchek crew. Another search team was sent out but nothing further was ever found.”

THE PRE-LEGION YEARS

Shortly after the Civil War, many veterans groups were established in towns and cities throughout the country and Marlborough was no exception. The first such organization in Marlborough was called the Veteran Soldiers. They met annually at the end of May in order to recognized and honor their departed comrades. This they called Decoration Day, a day of remembrance for those who have died in our nation’s service. There are many stories as to its actual beginnings, with over two dozen cities and towns laying claim to being the birthplace of Memorial Day. There is also evidence that organized women’s groups in the South were decorating graves before the end of the Civil War. Memorial Day was officially proclaimed on 5 May 1868 by General John Logan, national commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, in his General Order No. 11, and was first observed on 30 May 1868, when flowers were placed on the graves of Union and Confederate soldiers at Arlington National Cemetery. The first state to officially recognize the holiday was New York in 1873. By 1890 it was recognized by all of the northern states. The first written record of the Marlborough Veteran Soldiers appears in the Secretary Record of Veteran Soldiers dated 8 May 1880. It seems the group met annually during the month of May to vote for officers, conduct business, and plan for Decoration Day. This was a significant event for the town. Not only did the veterans participate, but also all the clergy from the different churches, municipal organizations, bands, and students. The first recorded Decoration Day in our possession is dated 30 May 1880 and reads in part – “The veteran soldiers net at the Town Hall at 9 o’clock AM accompanied by Torrent Engine Company, Sabbath schools of the different churches and led by the Mechanics Cornet Band marched through the principle streets to Granitville Cemetery. Prayer was offered by Reverend Polk after which the returned soldiers decorated the graves of their departed comrades and Comrade E. B. Holt read the Role of Honor.” By 1889, the terms Decoration Day and Memorial Day were being used interchangeably.

On 15 December 1980, Post 24 established Sons of the American Legion (S.A.L.) Detachment.

On 15 March 1999, Post 24 established an American Legion Auxiliary Detachment.

|

AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION |

Clarence J. CroteauPrivate, U.S. Army 358th Infantry Regiment, 90th DivisionEntered the Service from: New HampshireDied: September 26, 1918 Missing in Action or Buried at Sea Tablets of the Missing at St. Mihiel American Cemetery Thiaucourt, France Awards: |

|

COMMISSION |

Charles B. CouttsSecond Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Entered the Service from: New Hampshire |